Sometimes I Wish I Had Had an Abortion.

Recent Posts:

Luckiest Girl Alive; the Emotional Evolution of Men Should not be Bought at the Cost of Women’s Trauma

I've been traveling a lot for work and one of my favorite things to see is people watching planes on movies. No, I do not watch planes on movies, I prefer to watch other people watching movies. You can tell a lot about the person in 12C by the films they choose to watch on an 8-hour red eye from New York to London. Why would you watch the entire Need for Speed trilogy? Or what would compel the parent in 24F to put on the movie Chucky for their nine year old daughter. Sometimes the movie is auxilary to the real show; how people react to films on planes. Flying tends to bring out the best and the worst in people, and it's hard to look away when you see someone sobbing while watching Sharknado. A movie that I've recently seen a lot of people watching on planes is Luckiest Girl Alive, a recent film starring Mila Kunis, Finn Wittrock, Scoot McNairy, Thomas Barbusca, Jennifer Beals, and Connie Britton and is based on a novel by the same name.

The people who watch this film on planes are almost all women, and almost all of them have cried. As a result, it's been really hard to get myself to watch the movie because I, like most people, do not necessarily enjoy crying. While it can be soothing, cathartic crying can easily snowball into crippling sobs and bawling in the shower for twenty minutes. As a result, I've avoided most dramas in recent years and refuse to watch My Octopus Teacher. A movie that makes people swear off of eating Octopus might make me depressed enough to swear off eating anything, in general.

I've been traveling a lot for work and one of my favorite things to see is people watching planes on movies. No, I do not watch planes on movies, I prefer to watch other people watching movies. You can tell a lot about the person in 12C by the films they choose to watch on an 8-hour red eye from New York to London. Why would you watch the entire Need for Speed trilogy? Or what would compel the parent in 24F to put on the movie Chucky for their nine year old daughter. Sometimes the movie is auxilary to the real show; how people react to films on planes. Flying tends to bring out the best and the worst in people, and it's hard to look away when you see someone sobbing while watching Sharknado. A movie that I've recently seen a lot of people watching on planes is Luckiest Girl Alive, a recent film starring Mila Kunis, Finn Wittrock, Scoot McNairy, Thomas Barbusca, Jennifer Beals, and Connie Britton and is based on a novel by the same name.

The people who watch this film on planes are almost all women, and almost all of them have cried. As a result, it's been really hard to get myself to watch the movie because I, like most people, do not necessarily enjoy crying. While it can be soothing, cathartic crying can easily snowball into crippling sobs and bawling in the shower for twenty minutes. As a result, I've avoided most dramas in recent years and refuse to watch My Octopus Teacher. A movie that makes people swear off of eating Octopus might make me depressed enough to swear off eating anything, in general.

Luckiest Girl Alive is a movie about a highly ambitious, socially elegant young woman by the name of Ani, who has gone to the right schools, has the perfect job, and is set to be married to a gorgeous man in a perfectly gorgeous wedding. She doesn't eat carbs because she is disciplined, and her narration is the only clue we have to the fact that her entire outward persona is a sham. The narration we get reveals that she is spiteful, sarcastic, biting, and deceitful, while her outward appearance remains poised, controlled, and perfect. As the movie goes on, little by little we discover the complicated layers that make up Ani and her need for control and power. A documentarian has been trying to convince her to sit down to talk about her role surviving a school shooting; but, as flashbacks and her deteriorating mental health and stability show, there is much more to the story than that.

This movie is a gorgeous criticism of victim blaming, of purity culture, of women being told to protect and hide men from the consequences of their actions, because it would be a shame to ruin the life of 'a promising young man,' a phrase now made infamous because of its use in the trial of Brock Turner, a Stanford student who was caught raping an unconscious girl and was giving a mockingly light sentence for his crime. It peels back the layers of hypocrisy in our society that say that a man should be allowed to have sex with whomever he pleases, and that a woman should be flattered if he picks her, even if she doesn't want it. It forces us to confront that we would much rather women deal with the trauma of being a victim in silence and isolation, while men are allowed to use their victimhood to elevate themselves to hero status. It shows that if we are shown a man who is doing good and the shattered woman he broke on his way, we think it is a fair price to pay.

In a post #metoo era of reckoning, this film confronts how often we are more concerned that it will hurt men's feelings to be painted as the bad guys, than we are concerned with the wellbeing of the women they hurt. The film can be wrapped up in the final moments, when a fellow reporter who has followed Dean's career in campaigning for increased gun restrictions basically tells Ani that she has ruined things for everyone. Complicity is expected. Women are the stones that men sharpen themselves against, so they can do battle with anything other than themselves.

I was shattered when I watched this movie, which, as expected, I watched on a plane. Statistically, there were probably several women on my plane who have been victims of sexual violence. Statistically, there were probably several men on my plane who had been perpetrators of violence, But it comforts me to see Kunis's face on screen. Not in a romcom, but in a role with gravitas and meaning; a film that confronts what we don't want to talk about and is willing to splash it across the screens of hundreds of planes filling the sky. Perhaps if enough people watch it, if enough people are forced to confront the reality of what women are expected to suffer silently, maybe we will get somewhere and move the needle just a little bit forward.

Luckiest Girl Alive is a movie about a highly ambitious, socially elegant young woman by the name of Ani, who has gone to the right schools, has the perfect job, and is set to be married to a gorgeous man in a perfectly gorgeous wedding. She doesn't eat carbs because she is disciplined, and her narration is the only clue we have to the fact that her entire outward persona is a sham. The narration we get reveals that she is spiteful, sarcastic, biting, and deceitful, while her outward appearance remains poised, controlled, and perfect. As the movie goes on, little by little we discover the complicated layers that make up Ani and her need for control and power. A documentarian has been trying to convince her to sit down to talk about her role surviving a school shooting; but, as flashbacks and her deteriorating mental health and stability show, there is much more to the story than that.

This movie is a gorgeous criticism of victim blaming, of purity culture, of women being told to protect and hide men from the consequences of their actions, because it would be a shame to ruin the life of 'a promising young man,' a phrase now made infamous because of its use in the trial of Brock Turner, a Stanford student who was caught raping an unconscious girl and was giving a mockingly light sentence for his crime. It peels back the layers of hypocrisy in our society that say that a man should be allowed to have sex with whomever he pleases, and that a woman should be flattered if he picks her, even if she doesn't want it. It forces us to confront that we would much rather women deal with the trauma of being a victim in silence and isolation, while men are allowed to use their victimhood to elevate themselves to hero status. It shows that if we are shown a man who is doing good and the shattered woman he broke on his way, we think it is a fair price to pay.

In a post #metoo era of reckoning, this film confronts how often we are more concerned that it will hurt men's feelings to be painted as the bad guys, than we are concerned with the wellbeing of the women they hurt. The film can be wrapped up in the final moments, when a fellow reporter who has followed Dean's career in campaigning for increased gun restrictions basically tells Ani that she has ruined things for everyone. Complicity is expected. Women are the stones that men sharpen themselves against, so they can do battle with anything other than themselves.

I was shattered when I watched this movie, which, as expected, I watched on a plane. Statistically, there were probably several women on my plane who have been victims of sexual violence. Statistically, there were probably several men on my plane who had been perpetrators of violence, But it comforts me to see Kunis's face on screen. Not in a romcom, but in a role with gravitas and meaning; a film that confronts what we don't want to talk about and is willing to splash it across the screens of hundreds of planes filling the sky. Perhaps if enough people watch it, if enough people are forced to confront the reality of what women are expected to suffer silently, maybe we will get somewhere and move the needle just a little bit forward.

A Note About Texas

Sometimes when I write for this blog, I feel like I'm just another noise in an already massive echo chamber. I get discouraged, I feel invisible. I think to myself, 'maybe it's okay to be invisible, maybe you shouldn't have a voice in this.'

I've been writing since I was ten, and as a junior I started a magazine at my high school called The Voice. But I've always been shy about my writing; my poems are all small, crammed into tiny spaces as if someone was going to come and take up the rest of the page. My first chapbook was called Shy Knees. I rarely share my writing with other people, I rarely reach out to publications to ask them if I can write for them. I rarely even post on this blog. Some of it stems from fear. I don't want people to think I'm a bad writer. I don't want to read the mean and cruel comments that can sometimes follow the bottom of a post. I don't want to talk about myself. As a white-presenting middle-class woman living in San Francisco, I'm sometimes the last person in the world who needs to have an opinion on something. It's better for me to step aside and let other people have the floor.

I think, too, it's hard to tell when writing has impact. I've always loved to-do lists and I still have a bucket list I wrote over ten years ago that includes the missive "change someone's life." I wonder if I've ever done that with my writing. I wonder if anyone has ever read something I've put to paper and walked away feeling different, or feeling anything at all. Internally, I wonder if my writing has any impact on me. I've journaled nearly every day for the past three years, all of it introspective and self-analyzing, and I still feel like I miss the forest for the tiny trees; that I've made the biggest mistakes of my life in just the past week, and that while I wrote about being stressed at work or fights with my partner, my journal rarely touches on my sexual assault or my brother's incarceration, two of the most traumatic things that happened to me last year. I wrote about petty fights with my boyfriend, using words to store my bitterness in instead of using them as tools to break apart my outer hardness to find my vulnerability and gentleness inside.

I feel angry with myself. I feel like I've wasted time, or not been productive. I hate that I use the word 'productive' as much as I do. I take stress naps and wake up exhausted, and I check my bank balances every day because I have an anxiety that what I have will be taken from me at any moment. I feel shame, and I don't know for what.

I think this is all called exhaustion. I think this is all called being stressed and overwhelmed and not dealing with grief and taking too much on and ignoring the important things and losing the essential things and turning into the worst part of your parents and then fearing you're not turning into anything worthwhile at all. I want to be more quiet. I want to stare out the window more, I want to read on my couch for hours without worrying that I'm missing something. I want to put my phone in a box and put that box into the closet for the weekend. I feel guilty for not doing any of those things, and no pleasure in the things I am doing.

This is a long intro. This was supposed to be a post about how Texas is shitty and how, since The Voice, I've written about abortion access and rights. I wanted to write about how planned parenthood saved my life twice, by giving me information about my pregnancy that was fair and good and put me forward instead of the conservative agenda my dad put forward, that saw me as a sin and not a person. They saved me too, by giving me access to birth control I couldn't afford. I wanted to write something about all the different ways writing hasn't gotten us any closer to convincing people that maybe women shouldn't have to carry fetuses to term if they don't want to, that they exist as more than just reproductive machines.

But I just feel tired. So I'm keeping this space small, and safe. I am posting below some abortion funds that people can donate to if they feel so inclined, to help people access abortion care if it is no longer safe for them to do so where they live. And I want to hold space for the people who are exhausted and discouraged. It is okay to be like this. It is okay to want to stare at the wall for a little while. Let others take up the mantle when you no longer have the strength to do so. We will be coming back.

Abortion Funds:

The Whorticulturalist is the mother of this magazine. She is a sex-positive blogger and creative who enjoys rock climbing, dancing, and camping. In her spare time, she’s probably flirting.

La Impunidad: Disposable Women and Inexcusable Crime

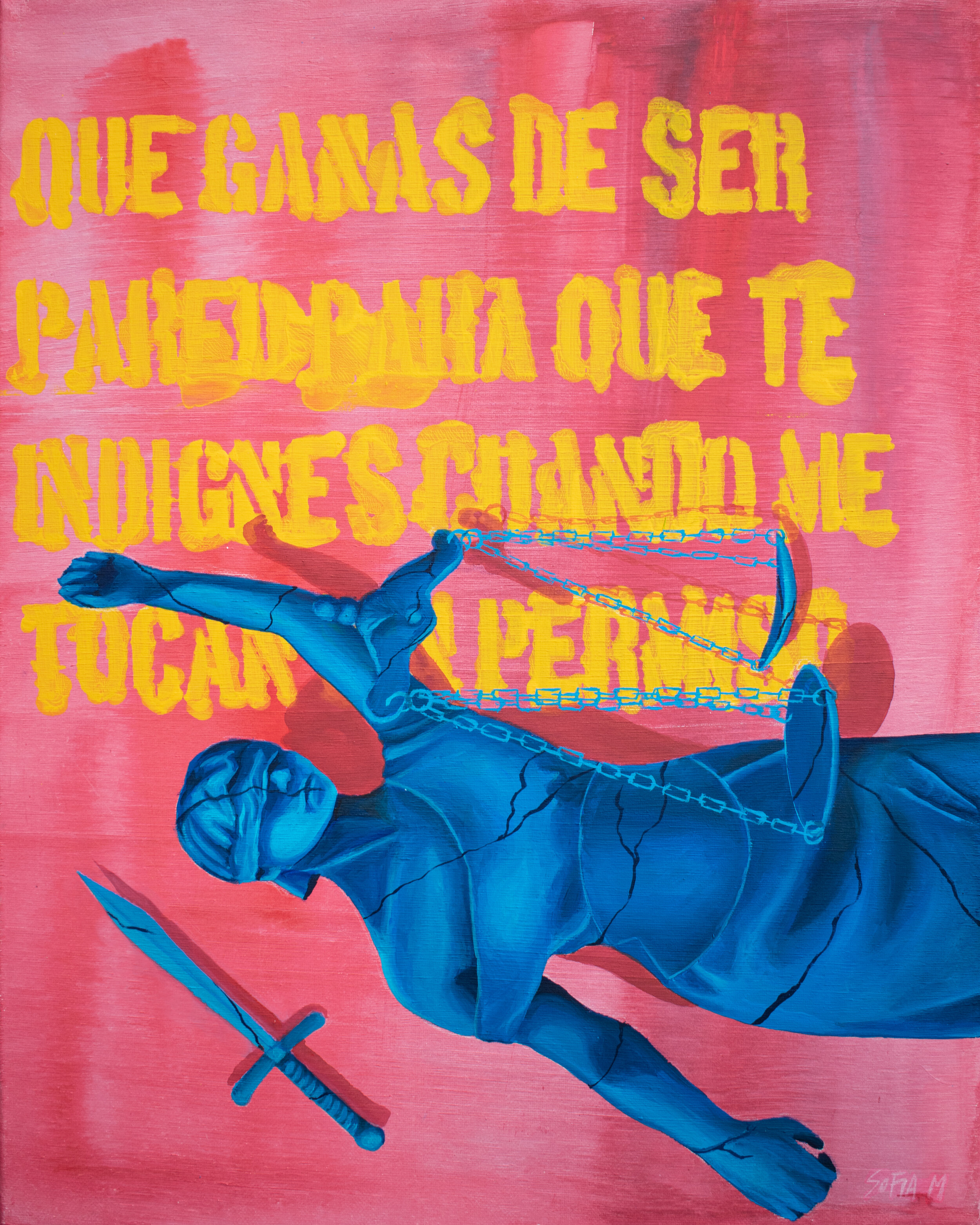

Art by Sofia Merino

On March 7th, 2017 the world awoke to a harrowing tale of 56 young girls burning inside an orphanage in Guatemala City, Guatemala. A nation already inundated with the burdens of gang violence, the news that broke that day reflected another, more insidious, form of brutality. This corrosive element has lurked in the background of Latinx politics at large since at least the 90s but this overt expression in Guatemala just before Women’s Day.

After a daring escape from their orphanage, the site of many traumatising acts, the girls were sequestered in a classroom by the police. With no permission to leave, the girls banded together to force the police to free them - they lit a mattress on fire. As the flames engulfed the room the police stood idly by allowing the brutal murder of 41 girls. This is the mark that Guatemala must bear. The blood of 41 young girls mars the hands of those officers. The burns that scar the skin of the living even moreso.

Years later no charges have been levied by the state, and many place the blame on the 15 girls that lived. The question is then begged - did their lives matter? Moreover, did their deaths?

The government made it clear that the answer is no. The weeks following the vicious act saw the government, headed by President Jimmy Morales, attempt to halt public mourning and dissent. These officers acted with impunity, an absolution from their acts granted to them by a justice system and a government entrenched in machismo.

Impunity has long been seen as a way of legitimizing violence, and when it comes to the violence enacted on women its role is immeasurable. Violence is often baked into the collective consciousness, the violence that we revile, the ones we condone, and the ones we endorse. Whether we think about it or not, we are constantly making allowances for the violence we see everyday, but sometimes the cruelty reaches a fever pitch.

The world stops, the people question, and the government makes a choice. In Guatemala the choice was clear, we stand with murderers not the murdered. To so boldly express a comfort with the flagrant acts of sadistic violence was a striking message for the thousands of other violent and hateful men that contribute to the nation’s atrocious femicide and gender-based violence rates.

Day in and day out the country’s justice system fails the thousands of women who have died and the millions who fear that fate. While the nation boasts the 7th highest femicide rates in the world the conviction rate for these crimes is dismal.

In 2008 the government actively changed the judicial process for the prosecution of crimes against women. At the time the changes were revered as a progressive way forward but just two years later it became apparent that something was amiss. The system that aimed to put women first still left over 99% of murderers unconvicted.

The question is why are perpetrators being absolved of their crimes?

Well, the answer is multifaceted. There are first financial barriers to accessing justice. The toll that legal fees take on the most affected communities cannot be neglected, especially in a country like Guatemala where inequality continues to skyrocket at a rate the government can’t possibly control. When women and the communities and families they belong to can’t access the justice system because of financial circumstances, it makes it impossible for justice to be carried out.

But even in highly publicised cases where lawyers are offering pro bono representation and people are fundraising by the millions, what happens? Where is the disconnect, what is halting justice?

Surely it can’t be the system itself, was specifically designed to benefit and support these women. If not the judicial process it must be the will of the people, it must be some unresolved resentment or conviction that keeps the judges, juries, and spectators from wielding the law for, and not against, the victims.

This culture of impunity incites crime. The violence, the fear, the impunity, it feels unstoppable because it is. Without punishment crime persists, indefinitely. Moreover, unpunished crime sends a message. These failures of the people, the government, and the system itself create a mosaic of severe injustice that perverts how the public understands crime as a whole.

Suddenly femicide is just something that happens, and again it filters into the background. All these acts we once thought too vile for cable news become movie titles and TV show plotlines. Yet another facet of life, yet another form of violence to accept, condone - even endorse.

At the state level this manifests in the impunity we see corroding our nations. In Latin America this results in thousands of unsolved and unmarked cases of femicide. For years, most countries failed to even have a category for these heinous crimes, even now that they do every level of the justice system continues to fail women dying at the expense of male ego and dominance.

Gender violence is both a mental and physical act. It is about how we think and why we can allow for gender based violence and femicide.

Mbembe first thought of necropolitics as a reaction to Focoult’s concepts of biopower. Asserting that the state not only necessitates and makes life possible, it also dictates how and who must die. Mbembe wrote about this in the context of late stage colonialism and colonial power, but necropolitics persist in every case of oppression.

In Guatemala, and more broadly with the region, it creates an air of disposability around women. When the state fails to give justice to the thousands of women who have died, it allows for their murder - encourages it even. It clearly says that women are who must die and at the hands of violent machista oppressor is how.

When those police officers made the active choice to sit idly by and allow those girls to burn to death they were empowered by decades of ignorance and allowances. The government had shown them, long before this moment, that it was comfortable with letting these acts slide. They were, in essence, perfect victims.

Young girls, with no family ties, and no clear futures. Nothing tethering them to the duties and responsibilities that crowd Latin femininity. Even if they had embodied that perfect image of "Una Buena Mujer", their deaths would be simply mourned by the state but not for the right reasons.

Art by Sofia Merino

All across Latin America, all across the world even, feminity is encumbered by notions of service and labour. At the same time in which labour is becoming increasingly decentralised, deregulated, and disposable. The free market has come to liberate us from basic understandings of human life. This liberation is coming at the cost of the bodies we see piling up in Guatemala and abroad.

Women are coming of age, and girls are coming into existence at a time where their lives have never meant less in the face of the cold unfeeling capitalist patriarchy. The question is not whether they will continue to die, it is whether their deaths will ever mean more than a headline.

The women on frontlines of this weaponization of machista culture are indigenous women. Existing on the intersection of such oppressed identities makes these women uniquely vulnerable to the boom and bust cycle that modern womanhood entails.

They are uniquely disposable because Guatemala has built a system that keeps them from participating in political and public life. After the tragic civil war that occured in the early 1960s to mid 1990s, that saw a (US backed) government cease the nation through a coup d’etat many indigenous peoples lost the necessary documents required for political participation. The then government specifically targeted leftist guerillas, indigenous, and rural communities to quell dissent against the neoliberal capitalist system they sought to impose.

With no way to run for office, vote, or truly be known as “Guatemalan” many indigenous women have fallen between the cracks. Just another way the state signals who must die, the erasure of these people from the Guatemalan identity pushes them out of the scope of community, of protection. That means more than just the formal protections of the state, the police, or the justice system, it extends into the social. The casual ways we attempt to protect and defend those we feel kinship with. It is clear that while the formal war is over, the fight for the extermination of indigenous peoples continues in the hearts of the bands of murderers forming misshapen guerrillas at night.

The marginalization of these women is necropolitics at work. The death tolls we are seeing climb, even in this time of great isolation, is evidence of its success.

Disposability is vital to understanding what anti-femicide activism is all about. Whether they are conscious of it or not the women who continue to pour into the streets, petition the government, and violently express their discontent are refuting a falsehood that has travelled the world long before they got here. Refusing any notion or understanding of their humanity that is rooted in temporary service and fleeting male pleasures. They are asserting their personhood in every way they can.

Indigenous feminists are at the forefront of this movement. An affront to the government, who under president Morales has called the feminist movement a public enemy. An affront to a society that would rather keep quiet. An affront to a culture that would see them dead before they see them as human. A fierce and formidable declaration that the nation can no longer hope to silence them. That they cannot hold back a wave of budding young feminists from standing up for themselves. Reflecting back to a machista society the very same foreboding assertiveness it has used against them.

As Pia Flores, a prominent Guatemalan journalist and feminist organizer, said in conversation with ReMezcla “Each of us resists in any way we can, every time we leave our homes”. That resistance is what keeps the state from winning.

Countless feminists movements have made their way to Guatemala, with each one women get one step closer to their future liberation. That oasis on the far side of the desert, what we all hope we will arrive at sooner rather than later. From #MeToo to “El Violador en Tu Camino” the power of global feminist organizing is perhaps best encapsulated by the fight in Guatemala. A mishmash of feminist movements that push the nation the precipice of freedom.

Impunity persists, but so does the resistance. A constant reminder that this fight won’t end until there is justice. Justice for those 41 girls that died and the over 2,500 that came after them. This nation can’t heal without resolution - with reckoning. This is what feminism in Guatemala has to be about, a constant search for reconciliation - an end to the violence.

Hayley is an emerging writer and journalist who works hard to create work that is fiercely feminist, anti racist and anti oppression on a whole. You can check out more of her work and content on her instagram @hayley.headley

This and Other Reasons Why I Don’t Walk Alone At Night

Artwork by Kay Sirianni

This poem was written at a time in my life where my mental health was fraying and I wanted to express my experiences and the experience of those around me. It gets into some deeply personal first-hand experience I have had with people who suffer from PTSD but my true purpose was to talk about the horrors of sexual assault and the mental scars it leaves behind. Sexual violence is a really horrible thing to experience, but the way in which PTSD prolongs victimhood consistently goes unspoken. So I spoke about it, and I hope it helps others understand that this is also a very female problem and many women are dealing with the traumatic aftermath on the daily.

Rape is like all the ‘nice’ guys I have ever met

He forces his way into your head, and then it's your bed

And now you can't rest

But before all of this

I never had this misfortune of meeting the man himself.

But now,

Now - Rape has moved in

Made a home for himself on the bed across the room

He bides his time during the day

Filters into the background

And at night he comes alive in the room

He haunts it

He preys on it

Hell, I think he enjoys it.

Sometimes I want to kick rape out

But I don't know where to start

When I try, he just comes back

He knows just when to show up

Knows how to wear us down

He makes it hard to keep living here.

Makes it harder to push him out

His shit is all over the place

Now my room is all stains and clutter and pain

Rape is tricky like that.

He comes back just when you think you are safe.

I wish Rape wasn't my problem anymore,

But he follows me now.

On my way home in the dark

Alone in my home

Around the men on the street

Rape,

Well he’s like all the nice guys I’ve ever met

Always there at the wrong moment.

Hayley is an emerging writer and journalist who works hard to create work that is fiercely feminist, anti racist and anti oppression on a whole. You can check out more of her work and content on her instagram @hayley.headley

Reap what you hoe.

Sign up with your email address to receive our latest blog posts, news, or opportunities.